From school prizes to writing his own novels, the author reflects on his lifelong bibliomania and explains why, despite e-readers and Amazon, he believes the physical book and bookshops will survive

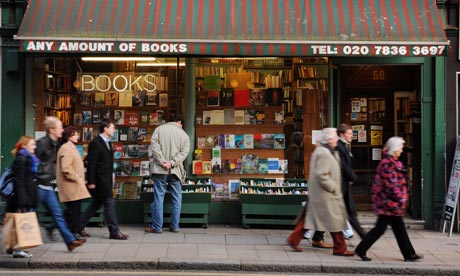

'To own a certain book – one you had chosen yourself – was to define yourself.' Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

I have lived in books, for books, by and with books; in recent years, I have been fortunate enough to be able to live from books. And it was through books that I first realised there were other worlds beyond my own; first imagined what it might be like to be another person; first encountered that deeply intimate bond made when a writer's voice gets inside a reader's head. I was perhaps lucky that for the first 10 years of my life there was no competition from television; and when one finally arrived in the household, it was under the strict control of my parents. They were both schoolteachers, so respect for the book and what it contained were implicit. We didn't go to church, but we did go to the library.

My maternal grandparents were also teachers. Grandpa had a mail-order set of Dickens and a Nelson's Cyclopaedia in about 30 small red volumes. My parents had classier and more varied books, and in later life became members of the Folio Society. I grew up assuming that all homes contained books; that this was normal. It was normal, too, that they were valued for their usefulness: to learn from at school, to dispense and verify information, and to entertain during the holidays. My father had collections of Times Fourth Leaders; my mother might enjoy a Nancy Mitford. Their shelves also contained the leather-bound prizes my father had won at Ilkeston County School between 1921 and 1925, for "General Proficiency" or "General Excellence": The Pageant of English Prose, Goldsmith's Poetical Works, Cary's Dante, Lytton's Last of the Barons, Charles Reade's The Cloister and the Hearth.

None of these works excited me as a boy. I first started investigating my parents' shelves (and those of my grandparents, and of my older brother) when awareness of sex dawned. Grandpa's library contained little lubricity except a scene or two in John Masters's Bhowani Junction; my parents had William Orpen's History of Art with several important black-and-white illustrations; but my brother owned a copy of Petronius's Satyricon, which was the hottest book by far on the home shelves. The Romans definitely led a more riotous life than the one I witnessed around me in Northwood, Middlesex. Banquets, slave girls, orgies, all sorts of stuff. I wonder if my brother noticed that after a while some of the pages of his Satyricon were almost falling from the spine. Foolishly, I assumed all his ancient classics must have similar erotic content. I spent many a dull day with his Hesiod before concluding that this wasn't the case.

The local high street included an establishment we referred to as "the bookshop". In fact, it was a fancy-goods store plus stationer's with a downstairs room, about half of which was given over to books. Some of them were quite respectable – Penguin classics, Penguin and Pan fiction. Part of me assumed that these were all the books that there were. I mean, I knew there were different books in the public library, and there were school books, which were again different; but in terms of the wider world of books, I assumed this tiny sample was somehow representative. Occasionally, in another suburb or town, we might visit a "real" bookshop, which usually turned out to be a branch of WH Smith.

The only variant book-source came if you won a school prize (I was at City of London, then on Victoria Embankment next to Blackfriars Bridge). Winners were allowed to choose their own books, usually under parental supervision. But again, this was somehow a narrowing rather than a broadening exercise. You could choose them only from a selection available at a private showroom in an office block on the South Bank: a place both slightly mysterious and utterly functional. It was, I later discovered, yet another part of WH Smith. Here were books of weight and worthiness, the sort to be admired rather than perhaps ever read. Your school prize would have a particular value, you chose a book for up to that amount, whereupon it vanished from your sight, to reappear on Lord Mayor's prize day, when the Lord Mayor of London, in full regalia, would personally hand it over to you. Now it would contain a pasted-in page on the front end-paper describing your achievement, while the cloth cover bore the gilt-embossed school arms. I can remember little of what I obediently chose when guided by my parents. But in 1963 I won the Mortimer English prize and, being now 17, must have gone by myself to that depository of seriousness, where I found (whose slip-up could it have been?) a copy of Ulysses. I can still see the disapproving face of the Lord Mayor as his protectively gloved hand passed over to me this notoriously filthy novel.

By now, I was beginning to view books as more than just utilitarian, sources of information, instruction, delight or titillation. First there was the excitement and meaning of possession. To own a certain book – one you had chosen yourself – was to define yourself. And that self-definition had to be protected, physically. So I would cover my favourite books (paperbacks, inevitably, out of financial constraint) with transparent Fablon. First, though, I would write my name – in a recently acquired italic hand, in blue ink, underlined with red – on the edge of the inside cover. The Fablon would then be cut and fitted so that it also protected the ownership signature. Some of these books – for instance, David Magarshack's Penguin translations of the Russian classics – are still on my shelves.

Full story at The Guardian

My maternal grandparents were also teachers. Grandpa had a mail-order set of Dickens and a Nelson's Cyclopaedia in about 30 small red volumes. My parents had classier and more varied books, and in later life became members of the Folio Society. I grew up assuming that all homes contained books; that this was normal. It was normal, too, that they were valued for their usefulness: to learn from at school, to dispense and verify information, and to entertain during the holidays. My father had collections of Times Fourth Leaders; my mother might enjoy a Nancy Mitford. Their shelves also contained the leather-bound prizes my father had won at Ilkeston County School between 1921 and 1925, for "General Proficiency" or "General Excellence": The Pageant of English Prose, Goldsmith's Poetical Works, Cary's Dante, Lytton's Last of the Barons, Charles Reade's The Cloister and the Hearth.

None of these works excited me as a boy. I first started investigating my parents' shelves (and those of my grandparents, and of my older brother) when awareness of sex dawned. Grandpa's library contained little lubricity except a scene or two in John Masters's Bhowani Junction; my parents had William Orpen's History of Art with several important black-and-white illustrations; but my brother owned a copy of Petronius's Satyricon, which was the hottest book by far on the home shelves. The Romans definitely led a more riotous life than the one I witnessed around me in Northwood, Middlesex. Banquets, slave girls, orgies, all sorts of stuff. I wonder if my brother noticed that after a while some of the pages of his Satyricon were almost falling from the spine. Foolishly, I assumed all his ancient classics must have similar erotic content. I spent many a dull day with his Hesiod before concluding that this wasn't the case.

The local high street included an establishment we referred to as "the bookshop". In fact, it was a fancy-goods store plus stationer's with a downstairs room, about half of which was given over to books. Some of them were quite respectable – Penguin classics, Penguin and Pan fiction. Part of me assumed that these were all the books that there were. I mean, I knew there were different books in the public library, and there were school books, which were again different; but in terms of the wider world of books, I assumed this tiny sample was somehow representative. Occasionally, in another suburb or town, we might visit a "real" bookshop, which usually turned out to be a branch of WH Smith.

The only variant book-source came if you won a school prize (I was at City of London, then on Victoria Embankment next to Blackfriars Bridge). Winners were allowed to choose their own books, usually under parental supervision. But again, this was somehow a narrowing rather than a broadening exercise. You could choose them only from a selection available at a private showroom in an office block on the South Bank: a place both slightly mysterious and utterly functional. It was, I later discovered, yet another part of WH Smith. Here were books of weight and worthiness, the sort to be admired rather than perhaps ever read. Your school prize would have a particular value, you chose a book for up to that amount, whereupon it vanished from your sight, to reappear on Lord Mayor's prize day, when the Lord Mayor of London, in full regalia, would personally hand it over to you. Now it would contain a pasted-in page on the front end-paper describing your achievement, while the cloth cover bore the gilt-embossed school arms. I can remember little of what I obediently chose when guided by my parents. But in 1963 I won the Mortimer English prize and, being now 17, must have gone by myself to that depository of seriousness, where I found (whose slip-up could it have been?) a copy of Ulysses. I can still see the disapproving face of the Lord Mayor as his protectively gloved hand passed over to me this notoriously filthy novel.

By now, I was beginning to view books as more than just utilitarian, sources of information, instruction, delight or titillation. First there was the excitement and meaning of possession. To own a certain book – one you had chosen yourself – was to define yourself. And that self-definition had to be protected, physically. So I would cover my favourite books (paperbacks, inevitably, out of financial constraint) with transparent Fablon. First, though, I would write my name – in a recently acquired italic hand, in blue ink, underlined with red – on the edge of the inside cover. The Fablon would then be cut and fitted so that it also protected the ownership signature. Some of these books – for instance, David Magarshack's Penguin translations of the Russian classics – are still on my shelves.

Full story at The Guardian